One bright May morning a couple of weeks ago, we drove from Athens to Milledgeville, Georgia, to see the home--now a National Historic Landmark--of the short story virtuoso, Flannery O’Connor. On the road we listened to a recording of the author reading her best-known short story “A Good Man is Hard to Find” for a lively audience at Vanderbilt University in 1959.

The narrative details the misfortunes of a family setting out from Atlanta for Florida in the family car—father and mother in the front seat, their two children and the grandmother in the back. The grandmother is chattering along the way and suddenly she has a senior moment, remembering a farmhouse that once harbored hidden gold. She convinces her son to go back and turn down a dirt road to see this house. Bumping down the rough road, the grandmother then remembers the location of the farm--in east Tennessee, not south Georgia. Startled, she kicks the basket at her feet, upsetting the family cat who jumps out of its hiding place and latches onto the son’s neck with her claws. The car flies into a ditch and flips.

Now enters “The Misfit,” a wanted criminal who steps out of the woods to inspect the damaged car and its occupants. The grandmother recognizes him from a newspaper account. The Misfit, she knows, is not a good man, and he orders his two accomplices to take the family, in pairs, into the woods. Gunshots later crackle from behind the trees.. The grandmother, now alone with the Misfit, unravels. She speaks kindly to him. She begs for his mercy, but he shoots her straight on, telling his accomplices: “She would have been a good woman if it had been someone to shoot her every day of her life.”

The last chilling lines and riotous applause for O’Connor’s droll reading of the story landed on us just as we parked the car in the new paved lot of the Visitor Center at Andalusia. This was the farm outside Milledgeville where O’Connor wrote most of her stories and two novels before succumbing to lupus in 1964 at the age of 39.

This year would have been O’Connor’s 100th birthday, and the writer’s local alma mater, Georgia College and State University (GCSU), which now operates the O’Connor house as a museum, is celebrating the occasion all year. O’Connor began her career in print as a cartoonist in college, and the new visitor’s center has mounted an exhibition of a significant number of O’Connor’s cartoons and paintings, some recently discovered after the family’s historic house in town was conveyed to GCSU as a gift from the writer’s elderly cousin. As the New York Times explained: “The painted caricatures were found in the attic around this time; the oil paintings had been crammed into a storage unit behind the drive-through of Cook Out, a fast-food restaurant.”

We saved the exhibition for last and began with a guided tour of the farm and 1800s farmhouse, where O’Connor and her mother lived together for 15 years. We were immediately taken with the vintage furnishings of the 1950s kitchen where the two women followed a daily routine of a simple breakfast, then drove to Catholic Mass in town. Back home from church, Flannery would isolate herself in her first-floor bedroom to write for three solid hours until lunchtime, while her mother ran the dairy farm from a makeshift office in the center of the house. Our tour guide, a student docent named Tatom Curtis, explained that Flannery and her mother usually went back to town for lunch at The Sanford House, a tearoom that operated in Milledgeville from 1951 to 1966. Her favorite meal, Tatom said, consisted of fried shrimp and “a chiffon.”

What’s a chiffon, you may ask? It’s a custard made airy by the addition of whipped egg whites. In the Sanford House recipe, the chiffon is also flavored by whimsically named “Starlight Kisses,” a signature southern candy that is shaped like a tiny hockey puck with red stripes radiating from the outer edges toward its pure white center.

The Sanford House was run by two women who met 30 miles away at Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia. Miss Fannie Appleby White was the college dietician, and Mary Jo Thompson was a student who worked in the dining hall. They opened their tearoom in Milledgeville when they leased an abandoned historical residence downtown that suited them. The restaurant soon made it to the “Gourmet’s Guide to Good Eating” and was conveniently situated next door to the Piggly Wiggly grocery store.

Flannery and her mother were regulars there and often brought literary guests for meals. Here is verbatim the somewhat complex but era-appropriate recipe for Flannery’s go-to dessert, as reproduced in The Sanford House Cookbook by Mary Jo Thompson, published by the Flannery O’ Connor-Andalusia Foundation, copyright 2008 (used by permission), and now available in the Museum gift shop.

PEPPERMINT CHIFFON PIE

¾ cup evaporated milk

¾ cup water

3 eggs, separated

1/8 teaspoon salt

whipped cream

6 Starlight kisses*

1 tablespoon plain gelatin

Keebler’s Chocolate Ready Crust

chocolate syrup

*Peppermint candies made by Southern Home—(or 1 ounce of any peppermint candies with corn syrup, sugar, and natural oil of peppermint.)

Soak gelatin in cold water. Combine milk and water and scald in double boiler. Dissolve candy in warm diluted milk. Beat egg yolks with ¼ cup sugar and add to scalded milk. Cook until mixture starts to coat spoon. Remove from heat and add gelatin. Set aside to cool. Beat egg whites until stiff but not dry while slowing adding ½ cup sugar. Carefully incorporate egg whites into the custard. Pour into chocolate shell and refrigerate. Spread whipped cream over top just before serving and dribble chocolate syrup over the cream. This is a most unusual dessert. Very light and a flavor you won’t forget, said the cookbook.

The New York food expert Valerie Stivers who writes the “Eat Your Words” feature in The Paris Review was skeptical when she first read this recipe. She made it, nonetheless, and reports: “You can’t make a bad peppermint chiffon pie. The Sanford House version was mild, minty, and just sweet enough. Topped with whipped cream and drizzled with chocolate syrup, it was heavenly.”

The Sanford House’s fried shrimp recipe is simple and a bit unusual. It calls for each shrimp to be peeled, deveined, and dredged individually in flour, followed by a dunk in buttermilk, and a roll in finely crushed saltine cracker crumbs before frying “in deep fat.”

If you are not inclined to try these recipes, we will report the outcome from the Food Pilgrim test kitchen, the recipes soon to be made for a dinner party. You have to admit, however, that the dessert is a total nostalgia trip, complete with melted candies and chocolate syrup.

The reminiscence is made more poignant by the fact that Flannery was a such grateful customer that she made the effort to write the tea room proprietors from her room at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta in late May, 1964, less than three months before she fell into a coma brought on by her lupus.

O’Connor praised the food she had enjoyed so often at the tearoom, “Up here,” she wrote from her hospital bed, “the pickings are meager in the food line. It tastes very well but there aint much of it—200 mg NA [dietary sodium] per meal—which suits my ailment but not my appetite.”

O’Connor died from kidney failure on August 3, 1964.

The trove of her paintings and other possessions exhibited in the Andalusia visitor center, now owned by GCSU, were as distinctive as her prose style and well worth the visit. Several new books are also out about the author/artist—a further testament to her literary longevity.

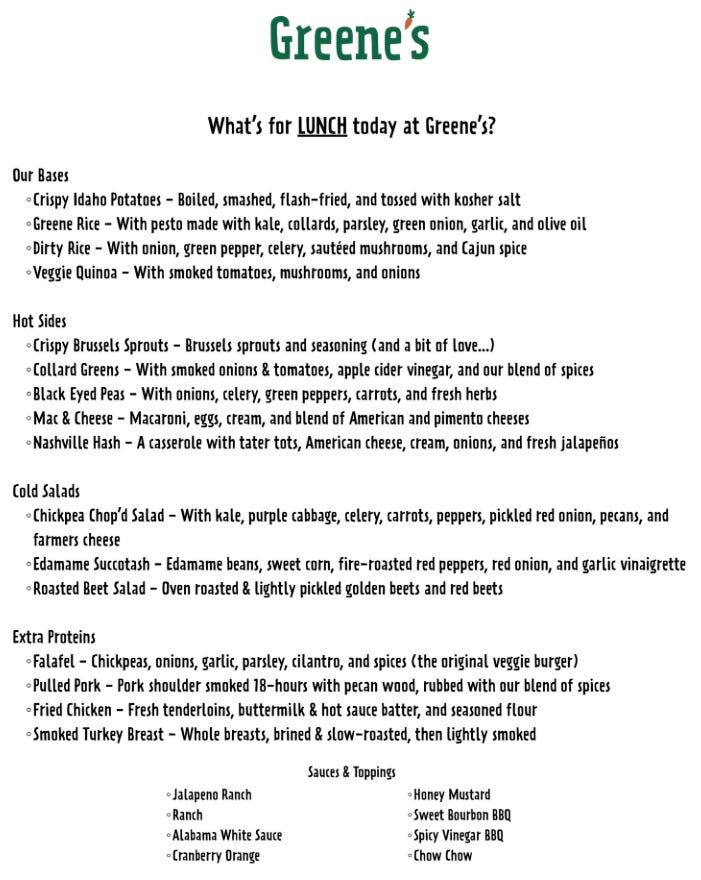

After our time at Andalusia, we found the contemporary answer to a great lunch in Milledgeville. At a small restaurant called Greene’s Farmhouse Foods, across the street from campus, the Greene brothers were dishing up delectable portions of southern tradition for eat in or take out, all served in recyclable paper containers with dividers. See the menu below. Their Mama was in the back making fresh buttermilk biscuits to die for. The food was healthful, not heavy, and outrageously delicious and priced fairly. Flannery would have enjoyed it.

Delicious and interesting. Food plus literary history all wrapped up in a road trip? Yes please. Thank you!

"...a such grateful customer." A such wonderful writer is Georgann Eubanks, and a such grateful reader am I. Thank you.