In 1940, when our friend Jimmy Milhous was six years old, he and his best friend Oscar both got bikes for Christmas. They were allowed to ride only around the corner and back from their neighboring houses in Atlanta. At the time, their Buckhead street was still being developed, offering lots of several acres that featured handsome homes of the era, many expansive with white columns, decorative shutters, and multiple fireplaces.

Jimmy’s young father, a banker in his 30s, raised chickens and rabbits in their backyard to supplement the family table. (This was still the Depression.) Jim Senior was also an accomplished woodworker, building formal furniture in his tool shed. On holidays and Sundays, Jimmy’s mother Hester often set a fanciful table with her fine china and silver service. Aspics and other molded gelatin desserts were a specialty of her house.

Recently, when we visited Jimmy and his wife Teri over the holidays, I had a chance to rifle through Hester’s recipes, written with a fountain pen in a cursive flourish on index cards. Hester doted on and coached her only child in the kitchen, and Jimmy thus inherited not only her recipe collection, but her love for the challenge of complex dishes and elegant southern cuisine.

Before they retired some years ago, Jimmy and Teri built a house out in the Georgia countryside and installed a restaurant grade oven and stovetop in their roomy kitchen, which overlooks a boiling patch of whitewater on the rocky Apalachee River. Every year on the day after Christmas for the last 25 years, Jimmy has greeted us upon our afternoon arrival with his mother’s secret recipe for eggnog, always topped with a four-inch froth and served in a silver punch bowl big enough to bathe a baby. A candlelight dinner of standing rib roast would follow, accompanied by a delicate Yorkshire pudding that Jimmy makes from the beef drippings. Side dishes of perfect potatoes, luscious gravy, green beans, and a most colorful congealed salad usually rounded out the menu.

Long before the meal, Jimmy would have also prepared his signature butterscotch cookies. After such a meal, we’d waddle outside to look at the December stars in the field beside the pecan grove, our warm breath rising toward the glittering sky.

This year, on the morning after, we gathered in the kitchen to fix a simple breakfast of coffee and English muffins. They were toasting in the big oven while Jimmy went rustling around in the pantry. He returned with a jar of something that was obscured in his large hands, and thus began the story of Jimmy and Oscar, their Christmas bicycles, and another kid that moved into their neighborhood in 1940.

“A new house had been going up near us—all brick—it was huge,” Jimmy said. “And then they added a smaller cottage to the side and put a brick wall around the whole property with a front gate. Oscar and I would ride by that wall and stop at the gate to look up the long driveway. We came to find out that the couple who built the house could not have children, so they adopted a little boy.” Jimmy’s accent, by the way, is all Georgia and molasses slow. He knows how to tell a story. We could smell the muffins browning as he went on.

“They hired a nanny to look after the boy, and Oscar and I would see her out on walks with him around the block. He was much younger than we were. One day she stopped and invited the two of us to come to her cottage on our bikes. She said we’d be having afternoon tea.” This sounded exotic to Jimmy. Surely it was something his mother would approve.

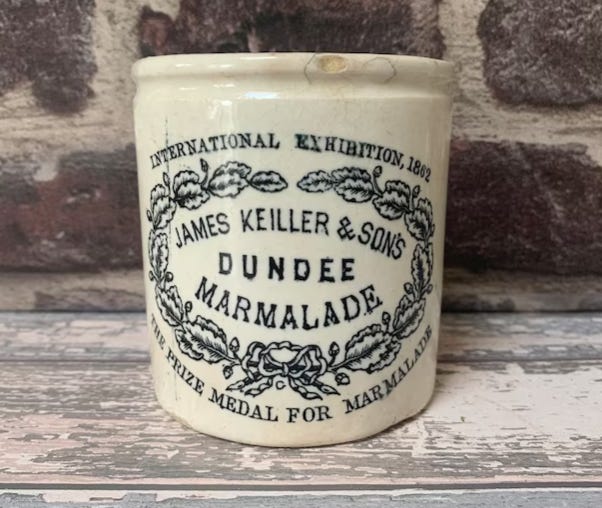

“It turned out that she served us biscuits and something I had never had before called marmalade.” Jimmy grinned and showed us the jar he’d fetched from the pantry.

The marmalade was a particular brand called Dundee. “The nanny was Scottish and so was the marmalade,” Jimmy explained.

As the Oxford Companion to Food describes it: “Marmalade in Britain refers to a jam-like preserve made from the bitter or Seville orange. The inclusion of the orange peel, cut into thin chips or shreds, is characteristic of this preserve.”

Historically, the most popular precursor to orange marmalade was made of quince--a fall fruit that is yellow, hard, and comes from a deciduous tree native to Greece, Iran and Turkey. Quince would be transformed in winter into a sweetened, solid paste that English speakers called marmalade--the first use of the term, derived from the Portuguese word for quince, which is marmelo.

Quince paste began as a luxury import to Britain in the fifteenth century, says the Oxford Companion. It was served as a dessert, a solid substance that was cut into slices and eaten with the fingers. Then citrus began being used—pulp and skin—to create “marmalades” that were more malleable and jam-like. (Both quince and bitter oranges contain a high amount of pectin which, along with sugar, are essential ingredients in jam and jelly making.)

“There is a strong traditional belief that Scotland was responsible for the creation of the new jellied orange marmalade,” the Oxford Companion explains. One apocryphal story suggests that a ship loaded with bitter Seville oranges from Spain was stranded in the Scottish harbor of Dundee in the late 1700s, and the mother of a local merchant named James Keiller turned the fruit into jam to sell locally. However, according to the contemporary Belgium-based food writer Regula Ysewijn, who blogs under the name “Miss Foodwise,” the earliest Scottish recipe for marmalade dates much farther back, to 1683. Nevertheless, by the mid-eighteenth century, Scottish recipes using oranges “and a higher proportion of water, giving a spreadable consistency” as Oxford puts it, became a popular breakfast staple in Scotland before the concoction ever caught on in England.

This narrative squares with what Jimmy learned from the Scottish nanny who took great pride in sharing her longstanding native treat with the boys.Though marmalade had gained prestige from its early association as a luxury import, it turned out to be an inexpensive and easy recipe for the working folk of Scotland who wanted to make something sweet in winter, when only citrus was available.

The Dundee brand is still celebrated after three centuries. Antique ironstone crocks and glass jars with the Dundee name affixed are prized worldwide by collectors, going for fancy prices today on Ebay and Etsy. Such is the power of taste and memory across lifetimes and oceans. Our dear Jimmy Milhous, who turns 90 this month, never buys any other brand.

SPECIAL NOTE: WHAT’S IN A NAME?

In our December post about the flight of sweet potatoes we sampled, the variety declared the best-tasting was called “Flaming Beauties” by the Carrboro growers at EcoFarm. This new variety is actually called NC-132 and was developed by the scientists at NC State University. Ask for it by that name.

We also have learned of a curious development that we previously missed on the same subject. Our good friend, the writer Jim Shamp, has explained in an article about NC agriculture that: In 2019, the North Carolina Sweetpotato Commission lobbied the general assembly to officially change the spelling of the state vegetable to “sweetpotato.” The measure passed and was signed into law by the governor. Advocates note that sweetpotato is a noun and not an adjective. They say “sweet” is not a descriptor, but part of the actual nomenclature for the vegetable technically known as Ipomoea batatas.

I’m still trying to digest this news.

Fascinating! I was just reading a thread somewhere the other day discussing jelly, jam, and marmalade. The consensus seemed to be that jam, and more often marmalade, was something many people as young children didn't have on the regular. The implication being jelly was more affordable and thus more frequently used.

That said, I'm adding your friends brand to my shopping list!

Lovely tradition, that meal, those friends…